I’ve got 3 invites for the 64 GB Sandstone Black model of the OnePlus One, about to expire on January 1, 2015. Comment or tweet at me.

Fedora 21 on XenServer

In this post:

Fedora 21 was just released earlier this week on December 9, 2014. The biggest change was the separation of the distribution into three “products”:

- Fedora Cloud, a lightweight optimized distribution for public/private clouds, containerization with Docker and Project Atomic.

- Fedora Server, the traditional platform for running services, usually on a headless host whether virtualized or on baremetal.

- Fedora Workstation, a developer-friendly desktop running a cutting edge OS.

Of course, as always, OpenStack/KVM and Docker get a lot of love, but Xen and XenServer are once again ignored. This post is my solution. With the prebuilt images distributed here and the kickstart scripts below, you can deploy Fedora 21 on your own XenServer (6.2+).

Continue reading “Fedora 21 on XenServer”

Found some old screenshots…

When I first came to Penn, the website for the Nominations & Elections Committee looked like this:

NEC website redesign

I set out to redevelop and redesign this, upgrading it from a static HTML site edited over SFTP to a WordPress CMS on Canvas. More importantly, the website redesign in 2012 needed to fit the rebranding that Penn underwent that academic year. In other words, I wanted it to look more like the university’s design. (An email to the Communications office responsible for web assets clarified that we could, in fact, do this.)

PGP key transition

I am transitioning PGP keys from an old 2048-bit RSA key to a new 8192-bit RSA master key with subkeys.

Continue reading “PGP key transition”

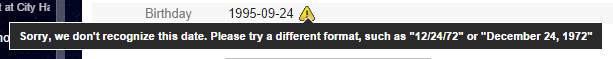

Google, you should know better

The YYYY-MM-DD format (%Y-%m-%d) is an internationally accepted, and standardized (ISO 8601) date format. The entire ISO 8601 system is based on big-endian ordering (greatest-to-least units) within the string, so… year, month, day, hour, minute, second. It makes a hell lot more sense than the American traditional MM/DD/YY format. So much so, in fact, that ANSI and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have both adopted it. In some countries, like China, the traditional format in the language follows the same big-endianness: 2006年1月29日, which spells out 2006-01-29.

The advantage of this format isn’t just for programmers, where sorting dates and times requires no special logic (i.e. 2014-01-31 unambiguously precedes 2014-02-01, even if they were both written without delimiter symbols).

The format also eliminates any confusion between the fields. For instance, though colloquial American 11/12/13 should be interpreted as November 12, __13, it could just as easily pass for December 13, 2011. There is no room for confusion in 2013-11-12.

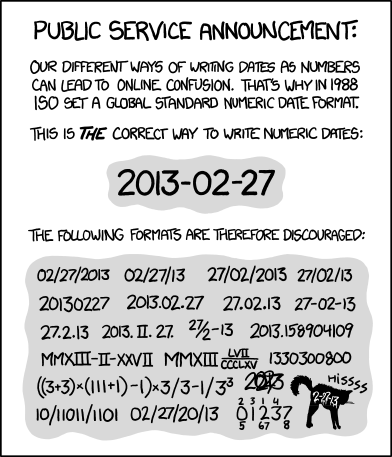

XKCD says it best:

Now, it’s understandable that maybe Google needs to recognize people’s different formats of entering dates in their colloquial formats, like MM/DD/YY. But there is no excuse not to recognize the YYYY-MM-DD format.

Even more so, because the date in my screenshot, 1995-09-24, has no possible misinterpretation. To any rational human being, there’s no way to think that this is the 9th day of the 24th month (!) of 1995.

PVHVM CentOS 7 on XenServer

In this post:

Following my previous post on running CentOS 7 and Ubuntu 14.04 as fully-paravirtualized guests on XenServer, I ran some benchmarks to compare the relative performance of fully-paravirtualized (henceforth abbreviated PV) domUs against HVM guests using paravirt drivers and interrupts/timers (henceforth PVHVM).

The performance differences between the two types has been studied for some time. Once upon a time, PV was undoubtedly faster, free of the overhead associated with full hardware emulation. With newer hardware features that have been supported for the last few years, PVHVM, which takes advantage of features in the processor as well as a Linux kernel that recognizes that it is operating as a virtual guest, has surpassed PV performance in most arenas.

Benchmarks

Benchmarks have severe limitations. The statistics here are only meant to be compared relatively among themselves—between the PV and PVHVM guests running exactly the same specs and software. It would be a futile exercise to compare them against VMs running on other servers, which might have better SANs, lighter workloads, or faster CPUs and RAM. The specific test profiles in the Phoronix software are also based on outdated versions of Apache httpd and nginx, which makes them unreliable for assessing real-world performance.

Some of the relevant comparisons:

It’s worth noting that CentOS 7 with a 3.10 kernel performed poorly compared to other distributions—both Fedora 20 (kernel 3.15) and Ubuntu 14.04 (kernel 3.13) outperformed CentOS on web serving workloads (not shown). But the evidence pretty conclusively showed that PVHVM generally performed better than PV on all of the operating systems.

Prebuilt image

Update (2017-04-28): Because these images are now out of date and insecure, the .xva images have been deleted. You should instead use the distribution’s latest cloud images in .qcow2 format, converted for XenServer.

To that end, I’d like to offer a prebuilt CentOS 7.0.1406 image that runs in PVHVM on XenServer. You should feel free to choose between this and the PV version from my previous post, depending on your needs. (If you need to accommodate higher density on your server, you might be better off with PV. Run benchmarks yourself to decide what you should use.)

As before, you can decompress (xz -d ___.xvz.xz or use your GUI of choice) then import through XenCenter (File – Import…) or the command line (xe vm-import filename=___.xva).

This image is provided with no guarantees. Please let me know in the comments if you find an issue with it.

- CentOS 7.0.1406 (as of 2014-07-31)

Filename:centos-7.0.1406-20140731-pvhvm-template.xva.xz

Size:325 MB xz-compressed; 1.4 GB decompressed

Specs:2 vCPUs, 2 GB RAM, 8 GB disk without swap, installed software, with XenServer Tools 6.4.93

SHA256 hash:c3ef221ae886cea4c3be09996d0cb2049dc2ac8f10dd5323f85beee25ce9d4cd

MD5 hash:44583aa3cdbf1db1c62b2db05530ce6f

Username:centos

Password:Asdfqwerty

Kickstart script

A PVHVM system requires no special accommodations when installing, except that UEFI and GPT are not certain to be supported. Merely select the “Other install media” option in XenCenter, and use a standard installer ISO/DVD. Do NOT use any of the CentOS or RHEL templates! Those will create PV guests.

An automated kickstart like the one used to create the image above may help you build a generic template. Hit <Tab> at the CentOS DVD menu and append a ks=__ parameter to use a kickstart script hosted at an HTTP location.

The image above was built with the cent70-server-pvhvm.ks script at revision e278f2a8139fb624bc2cdcd9a80d8b51b7910de3, embedded below. If there are any updates to this script, they will be added to the develop branch on GitHub. You can also edit it yourself before deploying.

[github file=/frederickding/xenserver-kickstart/blob/e278f2a8139fb624bc2cdcd9a80d8b51b7910de3/centos-7.0/cent70-server-pvhvm.ks][/github]

Did this help you?

If you were able to use this image or the kickstart, I’d appreciate a brief comment to let me know it worked for you. I’d hope that the bandwidth costs are going to good use!

Paravirtualized CentOS 7 and Ubuntu 14.04 on XenServer

Update (2015-10-21): since the images below have not been updated since July 2014, I highly recommend that you no longer use them; instead, you should use a kickstart script to install from the latest packages. Also, as I’ve noted in the comments, PVHVM will likely perform better overall. Update (2017-04-28): the .xva files have now been deleted; instead see this new guide for converting .qcow2 cloud images for use with XenServer.

One of the most frequently visited blog posts on my site is a guide to installing paravirtualized Fedora 20 on XenServer using an automated kickstart file. With the recent releases of RedHat Enterprise Linux 7 (and the corresponding CentOS 7 — versioned at 7.0.1406) and Ubuntu 14.04 LTS “Trusty Tahr”, as well as prerelease versions of the next iteration of XenServer, I thought it was time to revisit this matter and show you the scripts for optimized paravirtualized guests running the newest versions of CentOS and Ubuntu.

Table of Contents

- Prebuilt images

- OpenStack gripes

- XenServer version differences

- Kickstart scripts

- Installation instructions

Prebuilt images for the lazy

If you’re lazy, you can skip the process and download prebuilt XenServer images that you can decompress (xz -d ___.xvz.xz or use your GUI of choice) then import through XenCenter (File – Import…) or the command line (xe vm-import filename=___.xva). These images do not have XenServer Tools installed, because you should install them yourself using the tools that match your XenServer version.

These images are provided with no guarantees. Please let me know (comments below are fine) if you find an issue with them.

- CentOS 7.0.1406 (as of 2014-07-16)

Filename:centos-7.0.1406-20140716-template.xva.xz

Size:322 MB xz-compressed; 1.6 GB decompressed

Specs:2 vCPUs, 2 GB RAM, 8 GB disk without swap, installed software

SHA256 hash:ab69ee14476120f88ac2f404d7584ebb29f9b38bdf624f1ae123bb45a9f1ed94

MD5 hash:91e3ce39790b0251f1a1fdfec2d9bef0

Username:centos

Password:Asdfqwerty - Ubuntu 14.04 LTS (as of 2014-07-16)

Filename:ubuntu-14.04-20140716-template.xva.xz

Size:549 MB xz-compressed; 1.9 GB decompressed

Specs:2 vCPUs, 2 GB RAM, 8 GB disk including 1 GB swap, installed software

SHA256 hash:1c691324d4e851df9131b6d3e4a081da3a6aee35959ed3defc7f831ead9b40f2

MD5 hash:e2ed6cfb629f916b9af047a05f8a192d

Username:ubuntu

Password:Asdfqwerty

Side note on OpenStack

It’s true that private cloud IaaS tools like OpenStack have been growing in popularity, and increasingly, vendors are distributing cloud images suitable for OpenStack (see Fedora Cloud images). My instructions in the rest of this blog post won’t help you build images for an IaaS platform. You might as well just get the vendor cloud images if you’re going to be using OpenStack.

You can skip down to the next heading if you don’t want to read about my experiences with OpenStack.

OpenStack isn’t right for everyone

I tested out OpenStack + KVM on an HP baremetal server with 12 physical cores and 48 GB of RAM recently. Despite the simplified installation process enabled by RedHat, it didn’t fit my needs, and I went back to using XenServer. OpenStack was a mismatch for my needs and also has a few infrastructural problems, and hopefully someone reading this will be able to tell me if I’m out of my mind or if these are actually legitimate concerns:

- Size of deployment. Even though it can be used on a single baremetal server, OpenStack is optimal for deployments involving larger private clouds with many servers. When working with a single host, the complexity wasn’t worth my time. This is where admins need to judge whether they fall on the virtualization side or the cloud side of a very blurry line.

- Complex networking. Networking in OpenStack using Neutron follows an EC2 model with floating IPs, though there are various “flat” options that will more simply bridge virtual networks. The floating IP model is poorly suited to situations when the public Internet-routable network has an existing external DHCP infrastructure, and no IPs or IP ranges can be reserved.

- Abstraction. From what I could tell, there were ridiculous levels of abstraction. On a single-host node that hosts the block storage service (Cinder) as well as the virtualization host (Nova), an LVM logical volume created by Cinder would be shared as an iSCSI target, mounted by the same machine, and only then exposed to qemu-kvm by the Nova compute service.

- Resource overhead. The way that packstack deployed the software on a CentOS 7 server placed OpenStack—compute service (Nova), block storage (Cinder), object storage (Swift), image storage (Glance), networking (Neutron), identity service (Keystone), and control panel (Horizon)—and all its dependency components—MariaDB, RabbitMQ, memcache, Apache httpd, KVM hypervisor, Open vSwitch, and whatever else I’m forgetting—on the nonvirtualized baremetal operating system. That’s a ton of services, and attack surface, for the host… And the worst part: because each of those programs realized that the server has 48 GB of physical RAM, they all helped themselves to as much as they could grab. MariaDB was configured automatically with huge memory buffers; RabbitMQ seemed to claim more than 3 GB of virtual memory. By the time any virtual guests had been started up, the baremetal system was reporting at least 7-9 GB of used RAM!

That’s when I had enough. Technical benefits of KVM aside, and management capabilities of OpenStack aside, I decided to move firmly back into virtualization territory. XenServer’s minimal dom0 design and light overhead was much more suitable for my needs.

Note your XenServer version

XenServer Creedence requires no fixes

XenServer Creedence alpha 4—the most recent prerelease version that I am using—uses a newer Xen hypervisor and bundled tools. Consequently, it seems to have a patched version of pygrub that can read the CentOS 7 grub.cfg, which uses the keywords linux16 and initrd16, and which is no longer affected by the same parsing bugs on default="${next_entry}" that necessitated the fixes at the end of the post-installation script.

Fixes needed by XenServer 6.2

However, XenServer 6.2 cannot handle the out-of-box installation (ext4 /boot partition, GPT, etc) under paravirtualization without additional customization. Kickstart scripts are still the easiest way to ensure that the guests are bootable out of the box, by predefining a working partition scheme, selecting a minimal package set, fixing the bootloader script, and generalizing the installation.

Additionally, XenServer 6.2 lacks a compatible built-in template for Ubuntu 14.04. Thus, it cannot use netboot to install 14.04; you must use the 14.04 server ISO image to install.

The scripts to do it yourself

CentOS 7

I determined that the true minimal @core installation is too minimal for typical needs (it doesn’t come with bind-utils, lsof, zip, etc) so this image is installed with the @base group. About 456 packages are included.

[github file=”/frederickding/xenserver-kickstart/blob/develop/centos-7.0/cent70-server.ks”]

Ubuntu 14.04:

[github file=”/frederickding/xenserver-kickstart/blob/develop/ubuntu-14.04/trusty-server.ks”]

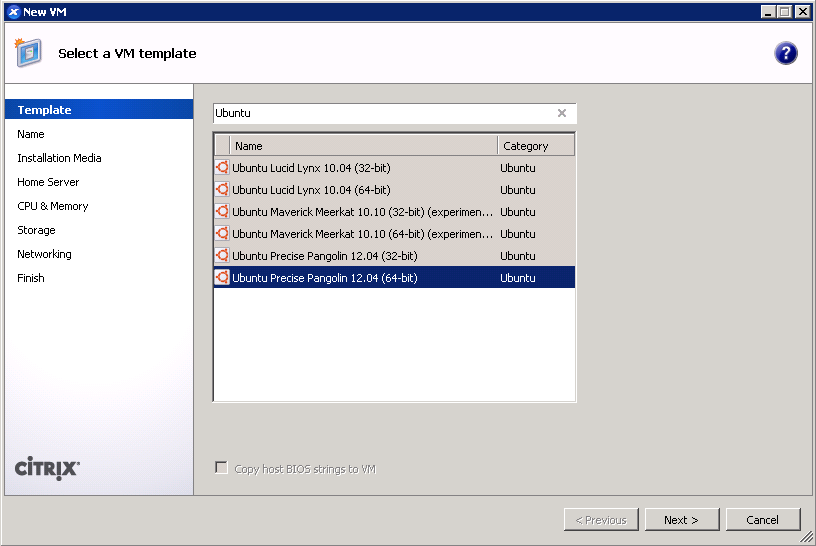

The process to do it yourself

CentOS 7

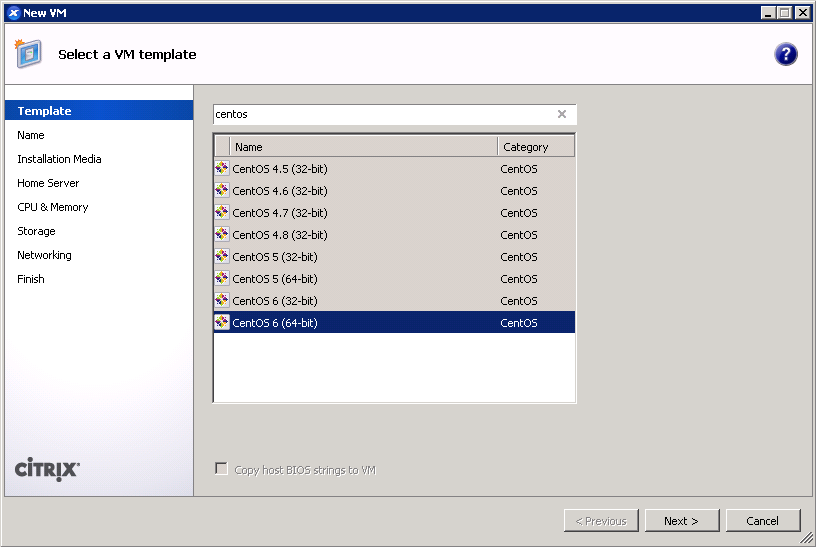

- Use the CentOS 6 template for a baseline.

- Give your VM a name. (screenshot)

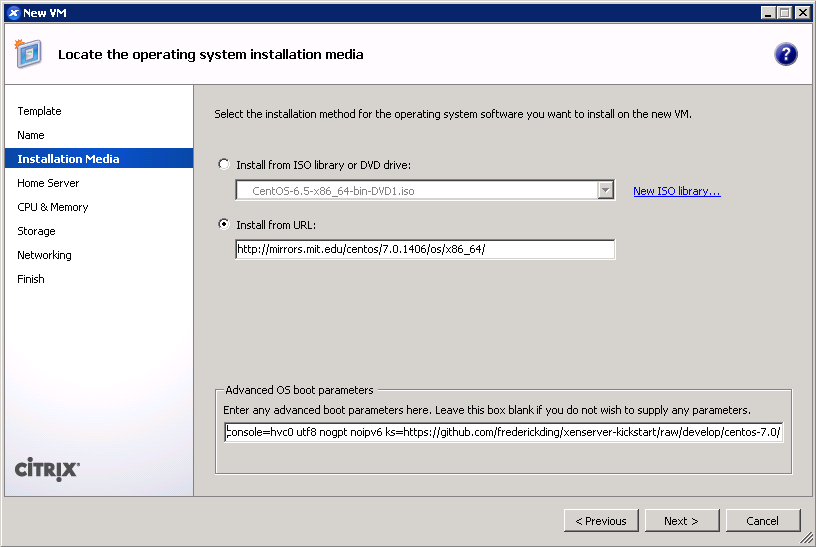

- IMPORTANT: Boot up a CentOS 7 installer with parameters. You can use the netboot ISO, or boot directly from an HTTP mirror (e.g. http://mirror.rackspace.com/CentOS/7.0.1406/os/x86_64/). This is also the screen where you specify the boot parameters:

console=hvc0 utf8 nogpt noipv6 ks=https://github.com/frederickding/xenserver-kickstart/raw/develop/centos-7.0/cent70-server.ks

Note: you may have to host the kickstart script on your own HTTP server, since occasional issues, possibly SSL-related, have been observed with netboot installers being unable to fetch the raw file through GitHub.

- Set a host server. (screenshot)

- Assign vCPUs and RAM; Anaconda demands around 1 GB of memory when no swap partition is defined. (screenshot)

- Create a primary disk for the guest. Realistically, you need only 1-2 GB for the base installation, but XenServer may force you to set a minimum of 8 GB. No matter what size you set here, the kickstart script will make the root partition fill the free space. (screenshot)

- IMPORTANT: Configure networking for the guest. It’s critical that this works out of the box (i.e. DHCP), since the script asks Anaconda to download packages from the HTTP repositories. (screenshot)

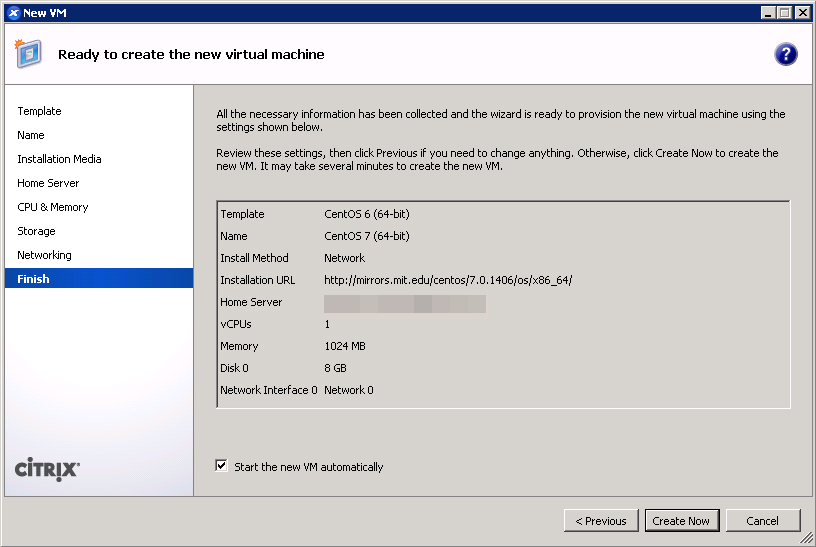

- Finish the wizard and boot up the VM.

- The VM will boot into the CentOS 7 installer, which will run without interaction until it completes.

- Press <Enter> to halt the machine. At this point, you can remove the ISO (if any).

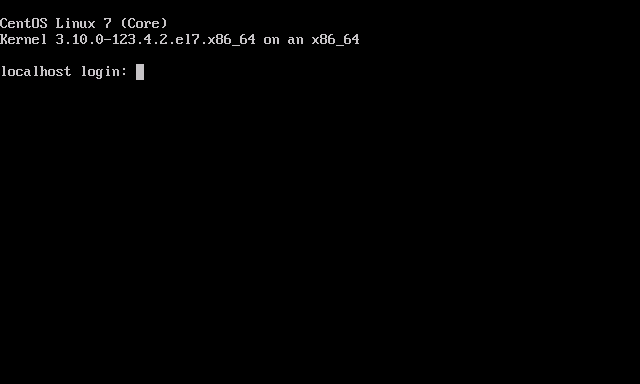

- Boot up the VM. It should go right into the login screen on the command line — from which you can do further configuration as needed.

Ubuntu 14.04

As mentioned above, this process will differ slightly if you are on XenServer 6.2 or older.

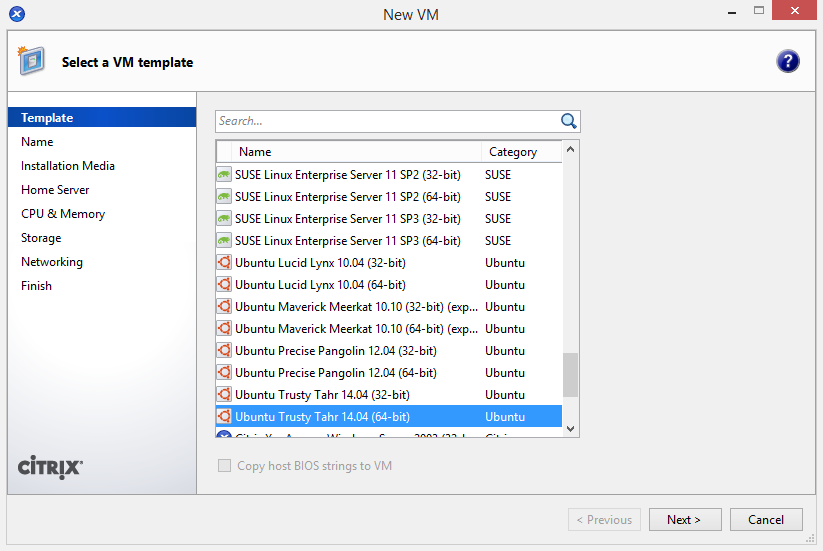

- On XenServer Creedence: Use the Ubuntu 14.04 template.

On XenServer 6.2 or older: Use the Ubuntu 12.04 template for a baseline.

On XenServer 6.2 or older: Use the Ubuntu 12.04 template for a baseline.

- Give your VM a name. (screenshot)

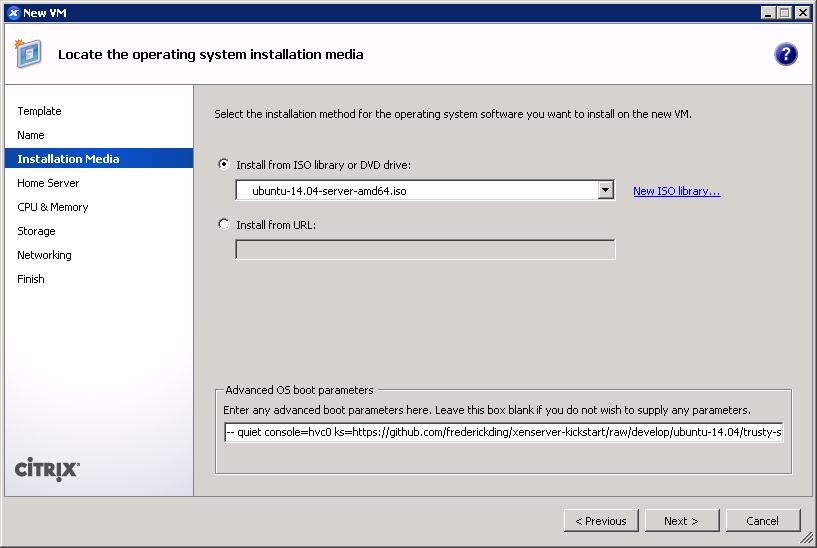

- IMPORTANT: On any version of XenServer: Boot up the 14.04 server ISO installer with parameters. You cannot use the netboot ISO.

On XenServer Creedence only: You can boot from an HTTP mirror, such as http://us.archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu/.

This is also the screen where you specify the boot parameters: append

This is also the screen where you specify the boot parameters: append ks=https://github.com/frederickding/xenserver-kickstart/raw/develop/ubuntu-14.04/trusty-server.ksto the existing parameters line.

Note: you may have to host the kickstart script on your own HTTP server, since issues, possibly SSL-related, have been observed with netboot installers being unable to fetch the raw file through GitHub. - Set a host server.

- Assign vCPUs and RAM.

- Create a primary disk for the guest. Realistically, you need only about 2 GB for the base installation, but XenServer may force you to set a minimum of 8 GB. No matter what size you set here, the kickstart script will make the root partition fill the free space.

- IMPORTANT: Configure networking for the guest. It’s critical that this works out of the box (i.e. DHCP), since the script asks the installer to download packages from online repositories.

- Finish the wizard and boot up the VM.

- The VM will boot into the Ubuntu installer, which will run without interaction until it completes.

Note: if you are warned that Grub is not being installed, you should nevertheless safely proceed with installation.

- Press <Enter> to halt the machine. At this point, you can remove the ISO (if any).

- Boot up the VM. It should go right into the login screen on the command line — from which you can do further configuration as needed, such as installing XenServer Tools.

Final thoughts

I recognize that these instructions require the use of a Windows program—XenCenter. I have not tried to conduct this installation using command line tools only. If you are a users without access to a Windows machine from which to run XenCenter, you can nevertheless deploy the kickstart-built XVA images above using nothing more than 2 or 3 commands on the dom0. If anyone can come up with a process to run through a kickstart-scripted installation using the xe shell tools, please feel free to share in the comments below.

I hope this has helped! I welcome your feedback.

What’s wrong with the Internet?

BuzzFeed is not known to be a shining beacon of quality journalism. It has a reputation for link-bait headlines (“38 Crazy Things You Never Knew About Kangaroos”) leading to GIF-laden lists. It publishes quizzes (answer a bunch of seemingly random questions before a script shows you the logical conclusion of your answers) so unscientific that no one should ever take them seriously for big life decisions.

BuzzFeed thrives on the short attention span of Generation Z—children born into an age when they can expect news to be spoonfed to them in bullet points and images.

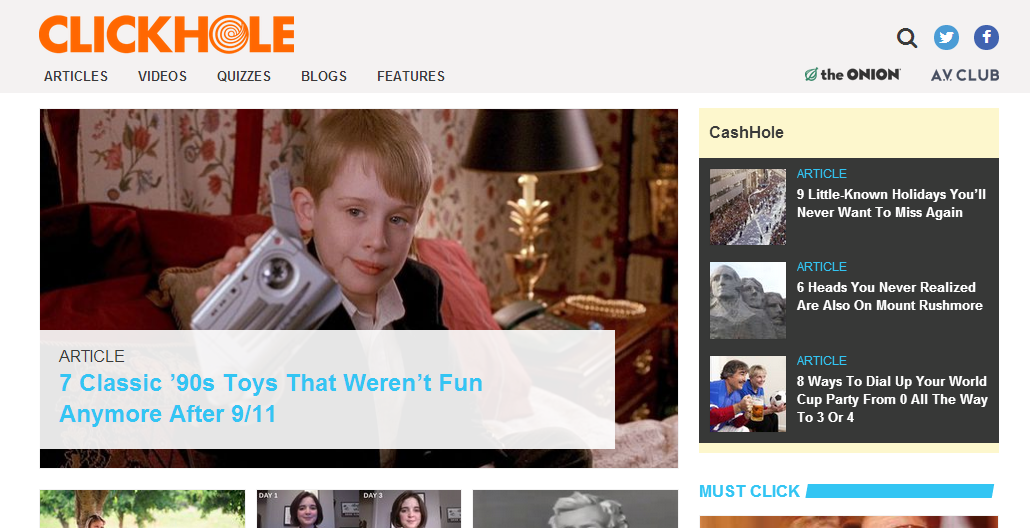

The people behind The Onion certainly saw right through this. They recently launched “ClickHole — Because all content deserves to go viral”, to parody both BuzzFeed and every other content-aggregating website that feeds on social media frenzies. (Worth mentioning: ClickHole parodies far more than BuzzFeed itself; it even incorporates references to “Upworthy, the feel-good viral-video site with a cloying habit of telling you what to think about its clips before you’ve even watched them.”)

But BuzzFeed has also published some high-quality longform pieces, dubbed BuzzReads. These are serious articles that cover the entire spectrum of subject matter, from politics, to technology, to rape and social justice. They’re of sufficient quality that they could easily pass for an extended newspaper exposé or magazine centrepiece. Targeting a more mature audience seeking longer reads, these feature stories often carry the same socially-liberal perspectives espoused by the rest of the site, while employing words more eloquent than their pop-culture GIFs could ever be.

I’ve had my doubts that BuzzFeed can sell itself in both markets. As great as the quality of their content may be, and as awesome as their access to reliable sources might be (the site has a DC operation with press pass access), it’s hard to “[break] down the divide between the light and the serious.” It’s a challenge the site’s editors realize:

“I think we need to show people that it’s up to us to write it in a way that has the context, has a compelling narrative to it. If you give them more of this and mix it in with fluff, and it’s treated equally by the publication, the public will start to treat it the same way too.”

Two years later, I think they’re starting to make some headway, at least among the social media users who are more publishers than consumers. People are sharing BuzzFeed’s longform essays on social media, using the site’s content to express beautifully the thoughts they could not write themselves.

What’s the reception like? I think many people on the consuming end of content are still sometimes skeptical. And I’m not sure that many people associate BuzzFeed sufficiently with quality content that they would be willing even to give reading BuzzReads a chance.

Case in point? This ignorant comment posted by a BuzzFeed reader on a post about the termination of American Apparel CEO, Dov Charney.

That article wasn’t even a longform essay. BuzzFeed had, through an anonymous leak, obtained an exclusive copy of the CEO’s termination letter, which no other news outlet reportedly had done. It was news, and it was worldly.

Apparently too worldly for this one commenter, who seems to think that only funny, entertaining, and “pertinent” (whatever that means in this context) content deserves to be published on a site from which they expect only entertainment.

I would be a fool to equate this one person’s opinion with everyone else’s. However, this is merely one example of the derisive attitude towards long online content I’ve witnessed first-hand—scroll through my Facebook timeline, or my friends’, and you will certainly find that GIFs and short interactive quizzes get more likes and click-throughs than essays about anything.

Why is that? It’s not like everyone is working 18-hour days in finance… Why don’t we, college students and young professionals, seem to have time for intellectual engagement outside of the classroom, on the Internet?

This old lady learns about the Internet for the first time, in Orange is the New Black—my newest favourite show. “But people are still stupid, right?” Indeed, the very technologies that made information so much easier to access, also made it easier to seek information in the shortest tidbits possible. Why read an entire screen of text, if you can get the essentials in 10 animated images?

There’s something deeply disturbing about this trend. It’s different—markedly different—from high school classes recognizing comic books as valid literature. This is a trend that makes education and self-expression more difficult, and less valuable in the eyes of this generation.

Media in our technological age must seek not only to earn pageviews, but also spark deep, insightful conversations about important contemporary issues. Instead of stooping to the lowest common denominator, as BuzzFeed seems to have done in its early launch, they have to champion the cause of literacy and engagement.

Why are genuine discussions about ethnic conflict or self-determination (indeed, a late-night discussion I’ve had quite a few times this week with my friends) outside of the academic environment so rare? Maybe, in part, it’s because of the Internet we consume.