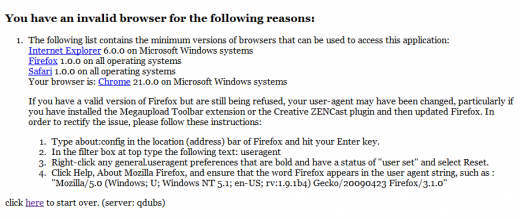

If IE6 (that ancient browser all web developers hate) works, I’m pretty damn sure Chrome 21 will!

It’s time they fixed this. Stop forcing me to launch Firefox!

Technology, law, life, and more.

If IE6 (that ancient browser all web developers hate) works, I’m pretty damn sure Chrome 21 will!

It’s time they fixed this. Stop forcing me to launch Firefox!

I haven’t had much time to blog recently — but more photos from Days 2-5 are coming soon.

I have neglected this blog for so long that I owe it to myself to post some more stuff here. Since I’m in China for about two and half weeks, I might as well blog about it — complete with photos*.

* I apologize in advance: most of the pictures are low quality photos from my cell phone.

From what I saw yesterday (let’s call it Day 0), items that are cheap in Canada and/or the United States can be insanely expensive here, while others that are reasonably expensive in Canada are dirt cheap here.

There’s a supermarket / department store chain called Carrefour that has everything imaginable, from imported milk to cell phones to oranges to suitcases. Asian ice cream bars can cost as little as $2 CAD for a package of multiple bars, while I saw a knife priced over ¥1500 and woks up to ¥809.

Aside: there’s an abundance of Engrish products, like “Woman Honey” and “Cuboid Sausage”.

Yet cab rides in Wuxi are dirt cheap. ¥15 brought four people from one side of town to the other — and I would probably estimate a bill of $15-20 USD (+tip) for the equivalent ride in Philadelphia. (I sometimes wonder how that money can possibly be enough to cover the insurance needed for such risky driving.) I’m told that public transit is even cheaper — something like ¥1 fares, not to mention seniors ride free.

The problem with the high prices here (inconsistent with purchasing power parity, which suggests that the price of a good here should be roughly the price of a good in Canada, for example, times the exchange rate) is that incomes are also lower in comparison. When nominal wages are low and prices are high, we come to the uncomfortable conclusion that real wages remain incredibly depressed for most citizens, and the inevitable result that the ordinary standard of living here still falls behind Canada and the US.

Restaurants can be pretty cheap. For breakfast today on Day 1, I went somewhere that is held in high regard for this particular type of breakfast/dim sum. ¥8 for a bowl of wonton, or for four meat buns (小笼包).

Aside: to eat 小笼包:

Aside: I thought this was tea — but it’s actually vinegar.

In essence, a delicious breakfast meal can be had for $3-4 USD — under the price of a Starbucks mocha in North America.

I’m a little afraid to be on the road here.

Also, there are mopeds everywhere.

On the bright side, Chinese people seem to have learned that there’s money to be made from taking risks and launching small businesses. There are lots of little shops of all kinds, many of them fashion or textile shops (people love to browse them but not buy from them). Some of these stores occupy the first floor of an otherwise decrepit building — but the shops themselves are nicely renovated and decorated.

On the opposite side, the income disparity seems to be increasing rapidly. Some alleys have people labouring to survive (e.g. cleaning shoes, fixing bike tires) while nearby streets boast Louis Vuitton stores and Häagen-Dazs ice cream.

Interestingly, rich and poor seem to coexist in the same spaces in Wuxi. Unlike the sharp divisions between good and bad neighbourhoods in some American cities (*cough* Philadelphia), it’s hard to find lower-income citizens in a place of their own.

I walked by an alleyway where construction workers probably lived. There was a cluster of people around something that resembled an outdoor food cart, but it wasn’t open to the general public — it was set up so that the community of laborers could eat affordably.

I’m going to post more photos from this venue in Part 2 of Day 1. We took somewhere between 250 and 300 photos of this historic site, where ancient architecture and estates from earlier eras, trees hundreds of years old, and an intricate system of stone wells that collect mountain water, have been preserved. I’m going to need some time to sort through the photos.

(My uncle, who teaches martial arts, served as a tour guide and explained the historical/cultural significance of many of the sights.)

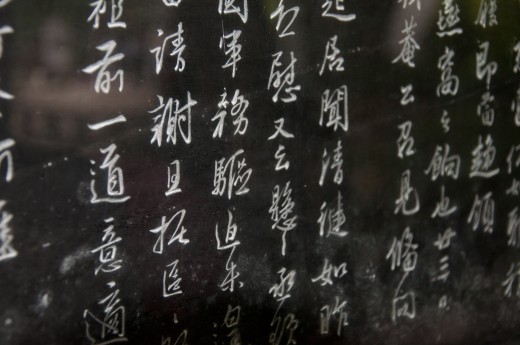

I also saw beautiful slabs of stone with engraved calligraphy, from different eras hundreds of years past. Even hundreds of years ago, the basis for the modern written Chinese language had already been set.

Anyways, all that and more will come — in Part 2.

Every pencil-and-eraser user’s greatest annoyance is getting rid of eraser shavings. The top YouTube result for “how to remove eraser shavings” is a rarely-viewed video (~300 views right now) showing the use of a compressed air canister:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZyeTmRqmvm8

Using compressed air to blow eraser shavings, or the simpler equivalent of blowing them off one’s desk… only move eraser shavings to the ground, where they will remain until you vacuum the floor. I don’t call that cleaning.

In the case that you don’t have a breadcrumb-type, portable handheld vacuum, try following my advice.

Yes, these things.

Roll one gently across the surface of a desk, and they’ll clean up eraser shavings as well as some of the dust. Peel off the sheet when you’re done and the eraser shavings will follow, into the trash, where they belong.

You can also use your favourite lint roller to remove dust and particles from your mousepad!

I’ve been attending classes for nearly three weeks here at the University of Pennsylvania, and in this short month I have already experienced many aspects of college life: meeting new people, making new friends, learning new things, trying new things, seeing new places, and so on… (This post was originally drafted in September 2011 but has been revised for December 2011; the new intro follows.)

Update (January 28, 2012): I’ve decided to remove password protection from this post and open it up to the world.

Update (December 2014): I’ve updated some of the campus photos, added links, and updated the objective factual statistics.

I just completed my first semester at the University of Pennsylvania. The past three months have brought me many joys: new friends, new experiences, and new knowledge. It’s been a rollercoaster of sorts—the cycles of stress due to impending exams, strange sleeping patterns, and a litany of decisions from picking courses to prioritizing assignments. It has been, however, rewarding.

For those who have not yet left the warmth and comfort of a family home, the most important thing to know is that university life is quite unlike high school life. (You probably knew that already, but I wanted to confirm it nevertheless.) Yes, there will still be classes with people you know, but lectures are much bigger, and it is entirely possible that TAs and professors will grade your papers/tests without ever meeting you face to face. Of course, university life is also different in that you will be running your own life. I’ll elaborate on this later.

For those who are experiencing university for the first time as well, it will be interesting to compare your experiences to mine. Every university has its own unique atmosphere, level of academic rigour, diversity of students, breadth of opportunities, and social climate. Of course, there are some common traits, such as students’ immense freedom, increased responsibilities (not only in time management, but in eating well, shopping for basic living needs, doing laundry, etc).

To anyone who is reading this post, I want to make it clear that anything subjective I write is only my personal opinion. My perception of Penn, or of college life, may differ significantly from that of someone else in a different social circle, program of study, or undergraduate school; it may also differ from that of someone who is living a (virtually) identical life. Even if I am experiencing something joyful at Penn, I cannot guarantee that you would make the same conclusions after the same experiences. The same goes for anything I complain about. Still, this post will contain objective information about the educational experience at the University of Pennsylvania.

Notice of Americanism: I will use the term ‘college’ to refer to four-year institutions, like the University of Pennsylvania, interchangeably with the term ‘university.’ Don’t let this confuse you, my non-American reader.

Let’s jump right into how I feel about life at university in general.

It’s ridiculously easy to get back into Canada from the United States, it seems, especially for a Canadian citizen.

“Where do you live?

“What were you doing in the States?

“What are you bringing with you?

“Any alcohol, tobacco, or controlled substances?

“Any weapons or firearms?”

Meanwhile, the guy is processing my passport in a reader. The whole interaction was under 20 seconds. Efficient enough, it seems.

When I entered the US on F-1 status, on the other hand, baggage had to go through an X-ray machine, questions were asked about fresh produce (why does that even matter), officers grilled other people for a long time, and the overall trip time gained about two hours from the border.

I don’t think there’s any difference in effective border safety/security on the two sides of this bridge.

Right now*, I stand among several dozen patients at Health Center #3, operated by the Philadelphia city government to provide clinical care to residents in a way that is available even to those without insurance or wealth. I’ve nearly been waiting for two hours for a quick skin test.

My alternative is Student Health Service, on another edge of campus, where there is a comfortable environment, shorter waiting times, and probably better trained personnel.

Instead of taking advantage of the benefits afforded to me by my student health insurance plan, a consequence of my attendance at the University of Pennsylvania, I chose this clinic because I could get the test done on an earlier date. I imagined it wouldn’t be as great of a place as SHS, or the expansive, top-tier hospitals of Penn Medicine, but what I am experiencing has convinced me, even more so than I thought before, of the epic failures of the American health care system.

* This post has since been revised and reformatted, although it was initiated during my time in the clinic.

[acm-tag id=”468×60″]

Those who are fortunate enough to have employer- or school-sponsored health insurance may have access to HMO hospitals, clinics, and doctors.

Those who attend a comprehensive university like mine may have access to the combined resources of a student health clinic and a set of university hospitals merely a block away.

Those who are in the lower strata of income and status, or whose recent unemployment leaves them uninsured, are relegated to public institutions such as these health centers, left to understaffed clinics, long wait times, and expensive, unaffordable medications. Some of these people are also caught outside the eligibility criteria of governmental programs like Medicare and Medicaid.

If timing weren’t an issue, I would just do this skin test back at home in Ontario, Canada. Sure, the skin test itself might not be covered by the provincial OHIP program, but at least every resident (after a certain number of months of residence) has access to physicians and walk in clinics at no basic charge beyond their taxes; those who are below the low-income cutoff might even pay $0 in federal and/or provincial taxes.

There is no such thing as a general practitioner who will turn you away because you “belong” to another unaffiliated insurance company. Low income citizens do not have to go to a crowded government “health center” for basic medical care; any privately-operated walk-in clinic, or a family doctor who is accepting new patients, will do. The UK also demonstrates how access to prescription medicine can be broadened.

Even those who are insured in the US are shocked when they find the cost of health care to be much higher than budgeted.

Even if we forget entirely about how much this sucks compared to medical care in Canada—which admittedly has its own issues—the disparities in access to, and quality of, health care between classes here in the United States should be appalling.

Dr. David Himmelstein of The Cambridge Hospital and Harvard Medical School, and his colleagues, authored a paper in the International Journal of Health Services in 2004 on the inefficiencies in the American health care system. One of the most potent conclusions is summarized in the abstract:

The United States wastes more on health care bureaucracy than it would cost to provide health care to all its uninsured … Only a single-payer national health insurance system could garner these massive administrative savings, allowing universal coverage without any increase in total health spending.

He also concludes that, in the US in 1999, “administrative spending consumed at least 31.0 percent of health spending… [i]n contrast, administrative costs in Canada… are about 16.7 percent of health spending.” I imagine some people are profiting from this spending.

I am a student, who, as a matter of circumstance (i.e. parents’ hard work) and fortune, have access to one of the top hospital systems in America. Not everyone is as fortunate. And it takes a bit of altruism to be able to stand up in a position like this and advocate on behalf of those who can’t.

Experience has shown that a weak populace is easier to rule over. One wonders if the goal of weakening the populace, especially the poor, is the reason that America continues to fail at reforming health care.