This post represents the views of the undersigned author only. You should consult a lawyer of your own if you want advice on your situation. See disclosures.

On April 1, 2023, Zoom sent an email to users stating that it had updated its Terms of Service. Purportedly those changes had an effective date of March 31, 2023—ponder how that works for formation of a valid contract, and just how much “bargaining” power consumers really had in that.[1]

If you are a Zoom user, you should opt out to preserve your rights in case a future dispute arises and you want to be able to sue them in real court (or benefit from a federal class action brought by others). Here’s how to do it:

27.11 Opt-Out. You may reject this Arbitration Agreement and opt out of arbitration by sending an email to opt-out@zoom.us within (i) thirty (30) calendar days of April 1, 2023 if you are an existing user, or (ii) thirty (30) calendar days of the date you created your account if you are a new user. Your opt-out notice must be individualized and must be sent from the email address associated with your individual Zoom account. An opt-out notice that purports to opt out multiple parties will be invalid as to all such parties. No individual (or their agent or representative) may effectuate an opt out on behalf of other individuals. Your notice to opt-out must include your first and last name, address, the email address associated with your Zoom account, and an unequivocal statement that you decline this Arbitration Agreement. If you do decide to opt out, that opt out will apply to this Arbitration Agreement and all previous versions thereof, and neither party will have the right to compel the other to arbitrate any Dispute. However, all other parts of this Arbitration Agreement will continue to apply to you, and opting out of this Arbitration Agreement has no effect on any other arbitration agreements that you may enter into in the future with us.

The new arbitration agreement is incredibly long—and different from what used to be standard arbitration provisions.

Unlike normal arbitration agreements of years past, which (simply) banned class actions and forced people to proceed individually and confidentially in arbitration, this version dictates what happens if a lot of customers individually sue in arbitration.

As explained below, the strategy of foreclosing class actions using mandatory arbitration backfired: highly motivated plaintiffs will still file their disputes individually. And paying lawyers and arbitration fees to fight against 12,500+ individual plaintiffs on 12,500+ individual cases is way more costly than litigating against one aggregated opponent, even if the ultimate recovery (e.g., damages award) being paid out is smaller.

So these contractual changes try to get back some of the efficiency of aggregation, while still denying people a chance to have that fight in real courts—courts that are accustomed to supervising class actions and deciding claims on an aggregate basis. Ask yourself: what’s the point? Why try so hard to avoid going to a real federal or state court, unless this works out better for the company?

“The [mandatory arbitration] system is set up to produce skewed, pro-defendant results, because defendants are buyers in the market for private judging: the initial choice of private judging over public dispute resolution belongs solely to the defendants. … This means that arbitration vendors’ biggest marketing incentive is to make arbitration attractive to defendants—more attractive than courts.”

David S. Schwartz, Mandatory Arbitration and Fairness, 84 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1247, 1338 (2009)

The new provisions say, in effect, that if more than 50 people represented by the same lawyers/organizations have similar claims against Zoom, 16 of them get hand-picked and decided first, while everyone else’s claims get paused. Once those 16 “bellwether” claims are decided, everyone else is then forced to mediate (i.e., negotiate), under the theory that the parties will likely settle based on how the bellwether cases fared.

Yet at the same time, the agreement provides separately that the outcome of any one arbitration (e.g., if a consumer wins against the company) shall have “no preclusive effect” in any other one—a rule that, if enforceable, is net helpful to the company because adverse rulings can’t be held against it and have to be re-fought each time. So if the claimants want to pursue their case, they still face the procedural hurdles of arbitration, like limited discovery, almost no option to appeal, and the unavailability of meaningful injunctive relief.[2]

Consumers already don’t read terms of service when they click through a sign-up online. Indeed, many “consumers are unaware of forced arbitration clauses … sometimes hidden inside of envelopes, delivery boxes, and privacy policies”—yet courts have enforced arbitration agreements against consumers who had no actual awareness of the provisions.[3] But how many people understand what this agreement is doing and what it means for their rights? Under what theory of the formation of a valid contract can we really say that a consumer—other than a savvy lawyer—knew what they were “agreeing” to?

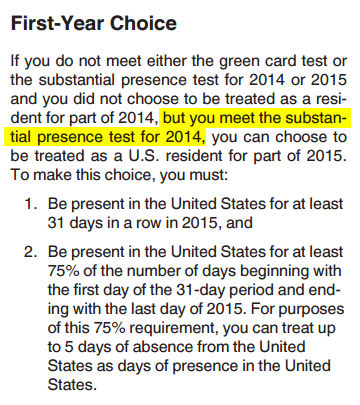

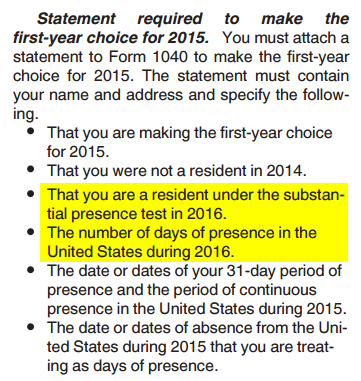

This quote shows how long some of the new provisions in Zoom’s arbitration agreement are—and it’s just an excerpt:

27.6 Mass Action Waiver. You and Zoom agree that, except as specified in Section 27.7 below, each of us may bring claims against the other only on an individual basis and not on a class, collective, representative, or mass action basis, and the parties hereby waive all rights to have any Dispute be brought, heard, administered, resolved, or arbitrated on a class, collective, representative, or mass action basis. Subject to this Arbitration Agreement, the arbitrator may award declaratory or injunctive relief only in favor of the individual party seeking relief and only to the extent necessary to provide relief warranted by the party’s individual claim. Notwithstanding anything to the contrary in this Arbitration Agreement, if a court decides by means of a final decision, not subject to any further appeal or recourse, that the limitations of this Section 27.6 are invalid or unenforceable as to a particular claim or request for relief (such as a request for public injunctive relief), you and Zoom agree that that particular claim or request for relief (and only that particular claim or request for relief) shall be severed from the arbitration and shall be pursued in the state or federal courts located in San Jose, California. This subsection does not prevent you or Zoom from participating in a class-wide settlement of claims. 27.7 Bellwether Arbitrations. To increase the efficiency of administration and resolution of arbitrations, you and Zoom agree that if there are fifty (50) or more individual arbitration demands of a substantially similar nature brought against either party by or with the assistance of the same law firm, group of law firms, or organizations within a one hundred and eighty (180) day period (“Mass Filing”), the parties shall select sixteen (16) individual arbitration demands (eight (8) per side) for arbitration to proceed (“Bellwether Arbitrations”). Only those sixteen (16) arbitration demands shall be filed with the arbitration provider, and the parties shall hold in abeyance, and not file, the non-Bellwether Arbitrations. Zoom will pay the arbitration provider’s costs for the sixteen (16) Bellwether Arbitrations. The statutes of limitation, including the requirement to file within one (1) year in Section 27.10 below, shall remain tolled when non-Bellwether arbitration demands are held in abeyance. While the Bellwether Arbitrations are adjudicated, no other demand for arbitration that is part of the Mass Filing may be processed, administrated, or adjudicated, and no filing or other administrative costs for such a demand for arbitration shall be due from either party to the arbitration provider. If, contrary to this provision, a party prematurely files non-Bellwether Arbitrations with the arbitration provider, the parties agree that the arbitration provider shall hold those demands in abeyance. All parties agree that arbitration demands are of a “substantially similar nature” if they arise out of or relate to the same event or factual scenario and raise the same or similar legal issues and seek the same or similar relief. Any party may request that the arbitration provider appoint a sole standing administrative arbitrator (“Administrative Arbitrator”) to determine threshold questions such as (i) whether the Bellwether Arbitration process is applicable or enforceable, (ii) whether particular demand(s) are part of a Mass Filing, and (iii) whether demands within a Mass Filing were filed in accordance with this Agreement, including Section 27.3. In an effort to expedite resolution of any such dispute by the Administrative Arbitrator, the parties agree that the Administrative Arbitrator may set forth such procedures as are necessary to resolve any disputes promptly. The Administrative Arbitrator’s costs shall be paid by Zoom. The parties shall work in good faith with the arbitrator to complete each Bellwether Arbitration within one hundred and twenty (120) calendar days of its initial pre-hearing conference. The parties agree that the Bellwether Arbitration process is designed to achieve an overall faster, more efficient, and less costly mechanism for resolving Mass Filings, including the claims of individuals who are not selected for a Bellwether Arbitration. Following resolution of the Bellwether Arbitrations, the parties agree to engage in a global mediation of all remaining arbitration demands comprising the Mass Filing (“Global Mediation”). The Global Mediation shall be administered by the arbitration provider administering the Bellwether Arbitrations. If the parties are unable to resolve the remaining demands for arbitration comprising the Mass Filing within thirty (30) calendar days following the mediation, the remaining demands for arbitration comprising the Mass Filing shall be filed and administered by the arbitration provider on an individual basis pursuant to the arbitration provider’s rules, unless the parties mutually agree otherwise in writing. Any party may request that the arbitration provider appoint an Administrative Arbitrator to determine threshold questions regarding the newly filed demands. The parties agree to cooperate in good faith with the arbitration provider to implement the Bellwether Arbitration process, including the payment of filing and administrative costs for the Bellwether Arbitrations, deferring any filing costs associated with the non-Bellwether Arbitration Mass Filings until the Bellwether Arbitrations and subsequent Global Mediation have concluded, and cooperate on any steps to minimize the time and costs of arbitration, which may include: (i) the appointment of a discovery special master to assist the arbitrator in the resolution of discovery disputes; and (ii) the adoption of an expedited calendar of the arbitration proceedings. This Bellwether Arbitration provision shall in no way be interpreted as authorizing a class, collective, or mass action of any kind, or an arbitration involving joint or consolidated claims under any circumstances, except as expressly set forth in this provision. The statutes of limitation applicable to each arbitration demand within a Mass Filing, including the requirement to file within one (1) year in Section 27.10 below, shall remain tolled from the time a party makes a Pre-Arbitration Demand to the time when that party files the arbitration demand with the arbitration provider. 27.8 Settlement Offers and Offers of Judgment. At least ten (10) calendar days before the date set for the arbitration hearing, you or Zoom may serve a written offer of judgment upon the other party to allow judgment on specified terms. If the offer is accepted, the offer with proof of acceptance shall be submitted to the arbitration provider, who shall enter judgment accordingly. If the offer is not accepted prior to the arbitration hearing or within thirty (30) calendar days after it is made, whichever occurs first, it shall be deemed withdrawn, and cannot be given as evidence in the arbitration. If an offer made by one party is not accepted by the other party, and the other party fails to obtain a more favorable award, the other party shall not recover their post-offer costs and shall pay the offering party’s costs from the time of the offer (which, solely for purposes of offers of judgment, may include reasonable attorneys’ fees to the extent they are recoverable by statute, in an amount not to exceed the damages awarded). The parties agree that any disputes with respect to settlement offer(s) or offer(s) of judgment in a Mass Filing are to be resolved by a single arbitrator to the extent such offers contain the same material terms. For arbitrations involving represented parties, the represented parties’ attorneys agree to communicate individual settlement offer(s) or offer(s) of judgment to each and every arbitration claimant or respondent to whom such offers are extended. 27.9 Arbitration Costs. Except as provided for in a Mass Filing (see Section 27.7), your responsibility to pay any filing, administrative, and arbitrator costs will be solely as set forth in the applicable arbitration provider’s rules. If you have a gross monthly income of less than 300% of the federal poverty guidelines, you may be entitled to a waiver of certain arbitration costs. 27.10 Requirement to File Within One Year. To the extent permitted by applicable Law, and notwithstanding any other statute of limitations, any claim or cause of action under this Agreement (with the exception of disputes under Section 27.2(2)) must be filed within one (1) year after such claim or cause of action arose, or else that claim or cause of action will be permanently barred. The statute of limitations and any arbitration cost deadlines shall be tolled while the parties engage in the informal dispute resolution process required by Section 27.3 above.

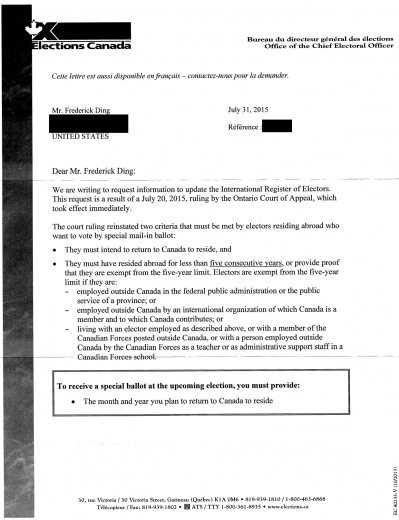

One other change of note: Whereas the older, short arbitration agreement elected to use the American Arbitration Association to decide claims, the new contract selects National Arbitration & Mediation (NAM).

Think about how the changes to the arbitration agreement reveal the imbalance in bargaining power on this supposed “agreement.” Zoom had the ability to purportedly replace its entire earlier arbitration agreement (“This Arbitration Agreement supersedes all prior versions.”)—but individual consumers have no such ability to do that. At any time, Zoom purportedly can change not just how claims are arbitrated but even who presides over the arbitration—but you, you normal person, you don’t get to do that.

In fact, Zoom even included a provision that you can’t even have an agent send your opt-out of arbitration on your behalf. You don’t get to use a lawyer. You don’t get to opt out for your minor child.

Your opt-out notice must be individualized and must be sent from the email address associated with your individual Zoom account. An opt-out notice that purports to opt out multiple parties will be invalid as to all such parties. No individual (or their agent or representative) may effectuate an opt out on behalf of other individuals.

Section 27.11.

To be clear, Zoom isn’t the only company making these changes. In recent months, Showtime (updated January 12, 2023), HBO Max (updated December 20, 2022), have all added similar mass-claim provisions that switch to using NAM as the arbitration provider. Query why they are all flocking away from AAA and JAMS to NAM, and what that suggests about what kind of incentives there are for NAM to differentiate itself from the other providers by being… more friendly to defendant companies?

And Showtime’s terms, most egregiously, even purport to limit discovery—making it that much harder for a claimant to get the internal evidence proving their claim.[4] And these agreements have suspiciously similar wording, suggesting that maybe the same lawyers are responsible for putting these changes in.

How we got here

Historically, class actions in courts allowed for aggregation of many claims (sometimes claims from people nationwide) in one case. Those rules were intended to enable efficient and fair resolution of disputes that share a common legal cause. That’s important where the actions of one national or multinational company could easily affect millions of users—and simultaneously harm millions of people with a common legal claim against the company.

To avoid mass torts and class actions, companies started putting in arbitration agreements to try to foreclose that type of lawsuit, achieving their own form of private tort reform. It is conventional for arbitration agreements to force claims to be arbitrated on an individual basis.

But clever plaintiff’s lawyers figured out how to game the system: if they had 1000 clients who were arguably harmed, they could file 1000 demands for individual arbitration, all following the express terms of the arbitration agreement. Since many agreements required the company to pay for the cost of filing the arbitration,[5] this strategy could rack up a giant bill for the company, to proceed with the arbitration.

12,500 Uber drivers did exactly that: filing many similar (even verbatim) claims individually against the company. That caused Uber to get in a legal fight with the arbitration provider, JAMS! Uber tried to weasel out of paying the arbitration fees by arguing that JAMS could aggregate the claims or work more efficiently on common issues.

Meanwhile, other companies that faced over 75,000 individual arbitration claims, decided to end their arbitration agreements altogether and revert back to going to court, as the New York Times reported. Again, query how exactly these contracts of adhesion can be imposed on customers—where the giant company can unilaterally decide to stop using arbitration by editing its terms, but individual customers have no choice.

Legislative reform on the horizon?

This all should be banned. And lawyers who are trying to take advantage of the system this way should really question whether what they are doing is good for their clients or good for the system. Egregious abuse of mandatory arbitration is a surefire way to attract the attention of legislators.

The 117th Congress took some action. The House of Representatives passed H.R. 963 (the FAIR Act of 2022) to end mandatory consumer arbitration. But that bill never made it through the Senate during that term.

The House Report observed:

Over the past several decades, forced arbitration clauses have become virtually ubiquitous in everyday contracts. Often buried deep within the fine print of employment and consumer contracts, forced arbitration deprives millions of Americans of their day in court to enforce state and federal rights. Because arbitration lacks the transparency and precedential guidance of the justice system, there is no guarantee that the relevant law will be applied to these disputes or that fundamental notions of fairness and equity will be upheld in the process.

Unlike the judicial system—in which courts’ decisions are generally public and, by building on precedent, cumulatively create a body of law—the results of arbitration disputes are often kept secret. …

Additionally, the company imposing arbitration often selects the presiding arbitrator or arbitration provider, creating a conflict of interest in which the purportedly neutral arbitrator may be motivated by the prospect of obtaining repeat business from the company rather than focused on fairly assessing the claim. …

As a result of the decline of enforcement of state and federal statutory protections, forced arbitration makes it more likely that corporate harms and abuse will go unchallenged. … as Professor Gilles observes, “forced arbitration is not an alternative regime for resolving claims, it is a means of suppressing legal claims altogether.” Judge William G. Young, who was appointed by President Ronald Reagan, likewise stated that the proliferation of forced arbitration clauses means that “business has a good chance of opting out of the legal system altogether and misbehaving without reproach.”

Forced Arbitration Injustice Repeal Act of 2022, H.R. Rep. No. 117-270, at 4-5 (2022).

It’s time for Congress to take up this bill again. Mandatory arbitration is systematically unfair to consumers, and these recent changes show just how far companies will go to press their advantage in this private system.

Footnotes

| 1 | ↑ | Section 15.1 says it’s your responsibility as a customer to monitor their contractual changes, and “If you continue to use the Services after the effective date of the Changes, then you agree to the revised terms and conditions.” Seems dubious if the effective date was before it told customers. |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | ↑ | “An arbitration award shall have no preclusive effect in another arbitration or court proceeding involving Zoom and a different individual.” Section 27.4. On its face, this could cut both ways, both helping the company avoid preclusive unfavorable rulings, and harming the company where favorable rulings should also apply to later claims. But under ordinary preclusion doctrines, some decisions that are favorable to the company can’t be held against future claimants who had no ability to participate in the earlier dispute or whose facts differ, whereas some decisions that are unfavorable to the company can be held against it despite the difference in the identity of the later claimant. On balance, this sort of rule probably skews slightly in favor of the company. |

| 3 | ↑ | H.R. Rep. No. 117-270, at 8-9 (2022). |

| 4 | ↑ | Section 1.3 (“Discovery During Arbitration”) in Showtime’s terms provides: “The parties shall each be limited to a maximum of one (1) fact witness deposition per side… Document requests shall be limited to documents that are directly relevant to the matter(s) in dispute or to its outcome; shall be reasonably restricted in terms of time frame, subject matter and persons or entities to which the requests pertain; shall not include broad phraseology such as ‘all documents directly or indirectly related to’; and shall not be encumbered with extensive ‘definitions’ or ‘instructions.’ … Electronic discovery, if any, shall be limited as follows. Absent a showing of compelling need: (i) electronic documents shall only be produced from sources used in the ordinary course of business, and not from backup servers, tapes or other media; (ii) the production of electronic documents shall normally be made on the basis of generally available technology in a searchable format that is usable by the requesting party and convenient and economical for the producing party; (iii) the parties need not produce metadata, with the exception of header fields for email correspondence; (iv) the description of custodians from whom electronic documents may be collected should be narrowly tailored to include only those individuals whose electronic documents may reasonably be expected to contain evidence that is material to the dispute; and (v) where the costs and burdens of e-discovery are disproportionate to the nature of the dispute or to the amount in controversy, or to the relevance of the materials requested, the arbitrator may either deny such requests or order disclosure on the condition that the requesting party advance the reasonable cost of production to the other side, subject to the allocation of costs in the final award.” How many consumers understand what the heck this is about? |

| 5 | ↑ | But see section 27.9 of Zoom’s arbitration agreement that now shifts those back to claimants. |