Excerpts from the Penn Engineering student survey…

SEAS survey: “I can cope with being the only person of my race/ethnicity in a class”

Me: “Not applicable”

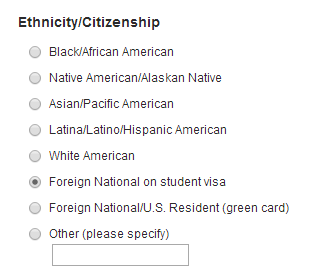

SEAS survey: select your ethnicity/citizenship…

Me: why are these mutually exclusive?!

Technology, law, life, and more.

Southwest Harbor, ME — I think. I wish I had a GPS device for this camera.

The following article was initially drafted with a guest author, Kirill Peretoltchine, at the end of July 2012.

A giant statue in the opening ceremony of the Athens Summer Olympics in 2004, onto which laser images of geometrical shapes and scientific concepts were projected, was a powerful reminder of a bygone era. Ancient Greece was a birthplace of logical thought, education, mathematics, science… and democracy.

The Renaissance was marked by an explosion in the diffusion of ideas, and the naissance of the scientific method that has allowed us to explore this world. This was the time of Copernicus, Galileo, Michelangelo, and da Vinci — the last of which, far from being just a scientist and artist, was also an engineer and writer: the stunning definition of a Renaissance man.

And one of the founding fathers of the United States of America, Benjamin Franklin — also the founder of our alma mater — was a polymath himself. Politician, scientist, writer…

There is a reason we honour and respect figures like da Vinci and Franklin, even if we, enlightened with 21st century practicality, do not expect to educate the entire populace in their image.

Both of us were shocked to read a real proposal by an educator at the City University of New York for the lowering of educational standards and the removal of mathematics from standard curricula.

We agree that there are serious deficits in the North American educational system that are in need of redress. We also concur that it is impractical to teach higher math effectively to every high school and college or university student. But we are firm in our belief that lowering the bar isn’t the answer. Andrew Hacker has a limited view of mathematics that fails to appreciate its value, and his solution of removing math from standards is flawed.

Continue reading “Lowering the bar on education isn’t the answer”

My friend just started a blog. This is one of its inaugural posts: Why I don’t want to go to med school.

I respect the majority of this article. I agree with most of it — the North American medical education system is clunky, and a ton of hurdles are thrown in the way of students who want to become doctors.

I’ve been attending classes for nearly three weeks here at the University of Pennsylvania, and in this short month I have already experienced many aspects of college life: meeting new people, making new friends, learning new things, trying new things, seeing new places, and so on… (This post was originally drafted in September 2011 but has been revised for December 2011; the new intro follows.)

Update (January 28, 2012): I’ve decided to remove password protection from this post and open it up to the world.

Update (December 2014): I’ve updated some of the campus photos, added links, and updated the objective factual statistics.

I just completed my first semester at the University of Pennsylvania. The past three months have brought me many joys: new friends, new experiences, and new knowledge. It’s been a rollercoaster of sorts—the cycles of stress due to impending exams, strange sleeping patterns, and a litany of decisions from picking courses to prioritizing assignments. It has been, however, rewarding.

For those who have not yet left the warmth and comfort of a family home, the most important thing to know is that university life is quite unlike high school life. (You probably knew that already, but I wanted to confirm it nevertheless.) Yes, there will still be classes with people you know, but lectures are much bigger, and it is entirely possible that TAs and professors will grade your papers/tests without ever meeting you face to face. Of course, university life is also different in that you will be running your own life. I’ll elaborate on this later.

For those who are experiencing university for the first time as well, it will be interesting to compare your experiences to mine. Every university has its own unique atmosphere, level of academic rigour, diversity of students, breadth of opportunities, and social climate. Of course, there are some common traits, such as students’ immense freedom, increased responsibilities (not only in time management, but in eating well, shopping for basic living needs, doing laundry, etc).

To anyone who is reading this post, I want to make it clear that anything subjective I write is only my personal opinion. My perception of Penn, or of college life, may differ significantly from that of someone else in a different social circle, program of study, or undergraduate school; it may also differ from that of someone who is living a (virtually) identical life. Even if I am experiencing something joyful at Penn, I cannot guarantee that you would make the same conclusions after the same experiences. The same goes for anything I complain about. Still, this post will contain objective information about the educational experience at the University of Pennsylvania.

Notice of Americanism: I will use the term ‘college’ to refer to four-year institutions, like the University of Pennsylvania, interchangeably with the term ‘university.’ Don’t let this confuse you, my non-American reader.

Let’s jump right into how I feel about life at university in general.

It’s ridiculously easy to get back into Canada from the United States, it seems, especially for a Canadian citizen.

“Where do you live?

“What were you doing in the States?

“What are you bringing with you?

“Any alcohol, tobacco, or controlled substances?

“Any weapons or firearms?”

Meanwhile, the guy is processing my passport in a reader. The whole interaction was under 20 seconds. Efficient enough, it seems.

When I entered the US on F-1 status, on the other hand, baggage had to go through an X-ray machine, questions were asked about fresh produce (why does that even matter), officers grilled other people for a long time, and the overall trip time gained about two hours from the border.

I don’t think there’s any difference in effective border safety/security on the two sides of this bridge.

Right now*, I stand among several dozen patients at Health Center #3, operated by the Philadelphia city government to provide clinical care to residents in a way that is available even to those without insurance or wealth. I’ve nearly been waiting for two hours for a quick skin test.

My alternative is Student Health Service, on another edge of campus, where there is a comfortable environment, shorter waiting times, and probably better trained personnel.

Instead of taking advantage of the benefits afforded to me by my student health insurance plan, a consequence of my attendance at the University of Pennsylvania, I chose this clinic because I could get the test done on an earlier date. I imagined it wouldn’t be as great of a place as SHS, or the expansive, top-tier hospitals of Penn Medicine, but what I am experiencing has convinced me, even more so than I thought before, of the epic failures of the American health care system.

* This post has since been revised and reformatted, although it was initiated during my time in the clinic.

[acm-tag id=”468×60″]

Those who are fortunate enough to have employer- or school-sponsored health insurance may have access to HMO hospitals, clinics, and doctors.

Those who attend a comprehensive university like mine may have access to the combined resources of a student health clinic and a set of university hospitals merely a block away.

Those who are in the lower strata of income and status, or whose recent unemployment leaves them uninsured, are relegated to public institutions such as these health centers, left to understaffed clinics, long wait times, and expensive, unaffordable medications. Some of these people are also caught outside the eligibility criteria of governmental programs like Medicare and Medicaid.

If timing weren’t an issue, I would just do this skin test back at home in Ontario, Canada. Sure, the skin test itself might not be covered by the provincial OHIP program, but at least every resident (after a certain number of months of residence) has access to physicians and walk in clinics at no basic charge beyond their taxes; those who are below the low-income cutoff might even pay $0 in federal and/or provincial taxes.

There is no such thing as a general practitioner who will turn you away because you “belong” to another unaffiliated insurance company. Low income citizens do not have to go to a crowded government “health center” for basic medical care; any privately-operated walk-in clinic, or a family doctor who is accepting new patients, will do. The UK also demonstrates how access to prescription medicine can be broadened.

Even those who are insured in the US are shocked when they find the cost of health care to be much higher than budgeted.

Even if we forget entirely about how much this sucks compared to medical care in Canada—which admittedly has its own issues—the disparities in access to, and quality of, health care between classes here in the United States should be appalling.

Dr. David Himmelstein of The Cambridge Hospital and Harvard Medical School, and his colleagues, authored a paper in the International Journal of Health Services in 2004 on the inefficiencies in the American health care system. One of the most potent conclusions is summarized in the abstract:

The United States wastes more on health care bureaucracy than it would cost to provide health care to all its uninsured … Only a single-payer national health insurance system could garner these massive administrative savings, allowing universal coverage without any increase in total health spending.

He also concludes that, in the US in 1999, “administrative spending consumed at least 31.0 percent of health spending… [i]n contrast, administrative costs in Canada… are about 16.7 percent of health spending.” I imagine some people are profiting from this spending.

I am a student, who, as a matter of circumstance (i.e. parents’ hard work) and fortune, have access to one of the top hospital systems in America. Not everyone is as fortunate. And it takes a bit of altruism to be able to stand up in a position like this and advocate on behalf of those who can’t.

Experience has shown that a weak populace is easier to rule over. One wonders if the goal of weakening the populace, especially the poor, is the reason that America continues to fail at reforming health care.